I disembarked the plane in Medellin, Colombia, and felt like I was home. It was neither a feeling of comfort nor familiarity, but one of belongingness. It’s rare that I feel so connected with the places I visit, but I generally fault myself for this. Frequently, I am the only blonde in a sea of brunettes, and if I can speak the native language, I do so in a mangled tongue that probably screams “ROB ME.” I have a weakness for bright-colored clothing and I typically can’t lift my own luggage. On the rare occasion that I do pack light, I don’t pack…right. One time I fashioned a bag that was not dissimilar to this for a backpacking trip across an entire continent:

Can we at least agree that there’s nothing cuter than a bag of babushkas?

Fortunately my best friend slapped that idea straight out of me and packed me a new bag. As they say, though, it’s hard to teach an old dog new tricks, and I’m afraid I’ll never be the most practical or muted foreigner. Medellin embraced me as I am, old tricks and all, and for this I tip my hat to the place.

Medellin, with its population of approximately 3.8 million, is a sprawling landscape nestled in the Northern Andes. Once described as the most dangerous city in the world for its drug-trafficking and high homicide rate, Medellin (or Colombia in general, actually) has a new face that some travellers seem slow to accept. Many attribute this facelift to the efforts of Sergio Fajardo, Medellin’s mayor from 2004-2007. Fajardo is a mathematician who attempted to fight crime by bringing educational opportunities to the poorest and most violent pockets of the city. He also invested in aesthetically overhauling these neighborhoods. As with any city, Medellin still has its problems, but thanks to Fajardo’s mayorship it is unrecognizable from the city it was in the eighties and nineties. Kidnappings, bombings, and shootings by motorcycle sicarios (hitmen) were all-too-common, and I talked to multiple people who vividly recall not being able to leave their homes after dark for fear of the above occurrences. Violence became the norm, and many who spoke out against its source were systematically obliterated.

While in Medellin, I reluctantly took a tour about Pablo Escobar’s influence on the city’s history. I seldom enjoy tours, but this one was presented as more of an interactive lecture than a herd of excitable tourists being shuffled from one landmark to the next. It was organized by local sociology students who aimed to deflate rumor and myth about Escobar with substantiated facts, inviting people to draw their own conclusions about the man. In the middle of our tour, a passerby mistook our purpose and started screaming at our guides, castigating them for making money by glorifying the infamous drug lord. One guide separated from the group to console the woman, who was now crying. He assured her that they were by no means sugarcoating Escobar’s persona, and he invited her along to witness this for herself. She politely declined and explained that one of the cartel’s bombs had ravaged her family’s home, and that she hated when people associated her city with the one thing that almost destroyed it. The guide later told us that many Colombians want to bury their past, but that as a sociologist, he believed that repressing these memories wasn’t helping the nation progress.

Virgin Mary shrine, where people would go to pray for protection from the violence.

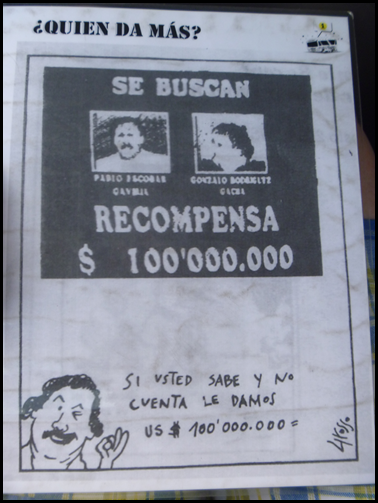

Reward for helping to find Escobar: 100,000 Colombian pesos. Reward for knowing where he was and not telling: 100,000 American dollars.

“Pablo lives!”

The tour was tactfully executed and extremely informative, and I appreciated that it neither exalted nor vilified Escobar. Any way you look at it, though, Colombians have survived an unimaginable internal war. It’s really easy for people (myself included) to sit in their cushioned environments and fleetingly think, “Sheesh, how sad that people had to go through that!” Sad doesn’t really cut it, though. The terror in that woman’s voice as she yelled at our tour guides was heart-wrenching, and it proved that the residual effects of the war are still palpable.

Just as this pain can be felt throughout the city, so can the unity amongst its people. Colombians are gregarious, intellectual, and eager to share the beautiful parts of their culture (which are many). The pleasant adjectives above don’t apply to Colombians that work in the Bogotá airport, but let’s ignore those anomalies for the sake of my argument in favor of all things Colombian. Medellin’s size can intimidate, but somehow, it feels like an inclusive, accessible place. I noticed right away that many of the city’s billboards were devoted to advertising cultural events as opposed to products, and there were flyers posted everywhere about support groups of all varieties. Whenever I took public transportation, I saw diverse groups of people engaging each other instead of partaking in the more insular activities of reading or listening to music. Gustavo Petro (Bogotá’s mayor) said, “A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It’s where the rich use public transportation.” Medellin definitely manifests this notion. The togetherness of its inhabitants adds to the warmth of the city, and helps to chip away the personal anonymity that can be felt in many large cities around the world.

Clearly, I can’t stop singing Medellin’s praises, but I hope you’ll allow me to drone on for just a trifle longer.

During my time there, three separate families that I met on the metro invited me to stay with them. And if you’re sarcastically thinking, “That sounds safe,” allow me to clarify that their invitations had not a hint of the, “I’m going to harvest your organs,” or “I can’t wait to watch you sleep” sensation. One time while I was walking on a dimly-lit street, I thought that a chancy-looking adolescent was preparing to mug me, when instead, he started tapping on a lamp post with his empty cola bottle while singing, “Welcome to Colombia.” I wanted to make out with him based solely on the fact that he had duped me so well. I also marveled at how many inspirational messages I saw tacked to service providers’ personal spaces. One grocery store employee had scribbled on the inside of her register, “You are only as good as your thoughts, as your thoughts become your actions.” I feel that Colombia is full of such positively-charged details, and Colombians have a zeal for living that I have detected in very few places.

Another resounding memory I have took place downtown in the Parque de los Pies Descalzos (Barefoot Park). Here, there are multiple fountains that you are allowed to wet your feet in, but apparently, it is prohibited to walk through them. These rules are not posted. It should come as no surprise to those who know me that I did not just walk, but frolicked rather heartily through said fountains.

Now, I’m no stranger to being reprimanded for public shenanigans ranging from trying to film a music video in a mall to sculpting bouquets out of flowers that didn’t exactly belong to me. However, never, before meeting this park official, have I been scolded in a way that could be described as charming:

Park official: Good afternoon, señorita. How are you enjoying this nice weather?

Lindsay: It’s pretty much my favorite, thanks for asking.

PO: I’m so glad Medellin is treating you well. Are you from here?

L: Was that a joke?

PO: No, your Spanish is excellent.

L: Now we both know that’s not true, but thank you.

PO: Señorita, I regret having to tell you this, but we are not allowed to let people walk through the fountains.

L: Oh, I’m sorry!

PO: No need to apologize. If anything, I’m sorry to have ruined your walk.

Parents everywhere, take note. My pal in the park just revolutionized the concept of discipline. Now don’t say I never told you that Colombians are the smartest!

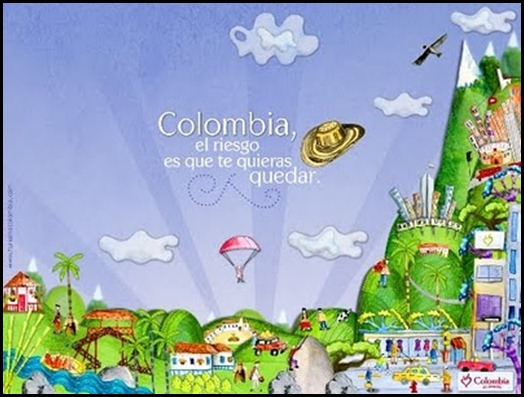

While my posts are usually bursting at the seams with food descriptions, I found Colombia to be too dynamic to dive right into its cuisine. I hope these cultural descriptions have effectively whet your appetite so that next time, you’ll be ready to tackle a visit to Cartagena and a rundown of palatable plates. Let’s conclude with a few more Medellin pics, along with a Colombian travel ad that I think is apropos.

This ad says, “Colombia, the risk is that you’ll want to stay.” This is true. The other risk is that you’ll never stop babbling on about it (case in point: this post).

I leave you with this recommendation: take the risk and go.